cleaning/writing/tidying/editing

it gets worse before it gets better

It is not a Sunday but I am watching someone do their ‘sunday reset’ on TikTok in which they clean their beautifully designed minimal studio flat in East London, or Manchester or Bristol or Margate to prepare for the week. By my standards it is already clean. It is much easier to watch someone else clean their flat than it is to clean your own flat and so I watch the whole thing. They change their sheets and clear their nightstand of clutter. They spray an obscene amount of antibacterial foam onto their kitchen counter and wipe it away. With a cordless vacuum cleaner, they thrust back and forth over their artful ‘Mid-century Millennial’ rug. With a different cordless handheld vacuum cleaner, they sweep their fabric sofa, spray it with something expensive looking, and replace the cushions by doing a karate chop in the centre of each of them. The sound of their cleaning has been sliced into relentless one-second ASMR slaps of noise. It makes for compelling viewing. Should I be changing my sheets once a week? Do I need a hoover just for my sofa? For a moment my sense of self rolls away from me and I am left suspended. Would this make me a better person? Would I be happier?

No, I think. No. I hate cleaning.

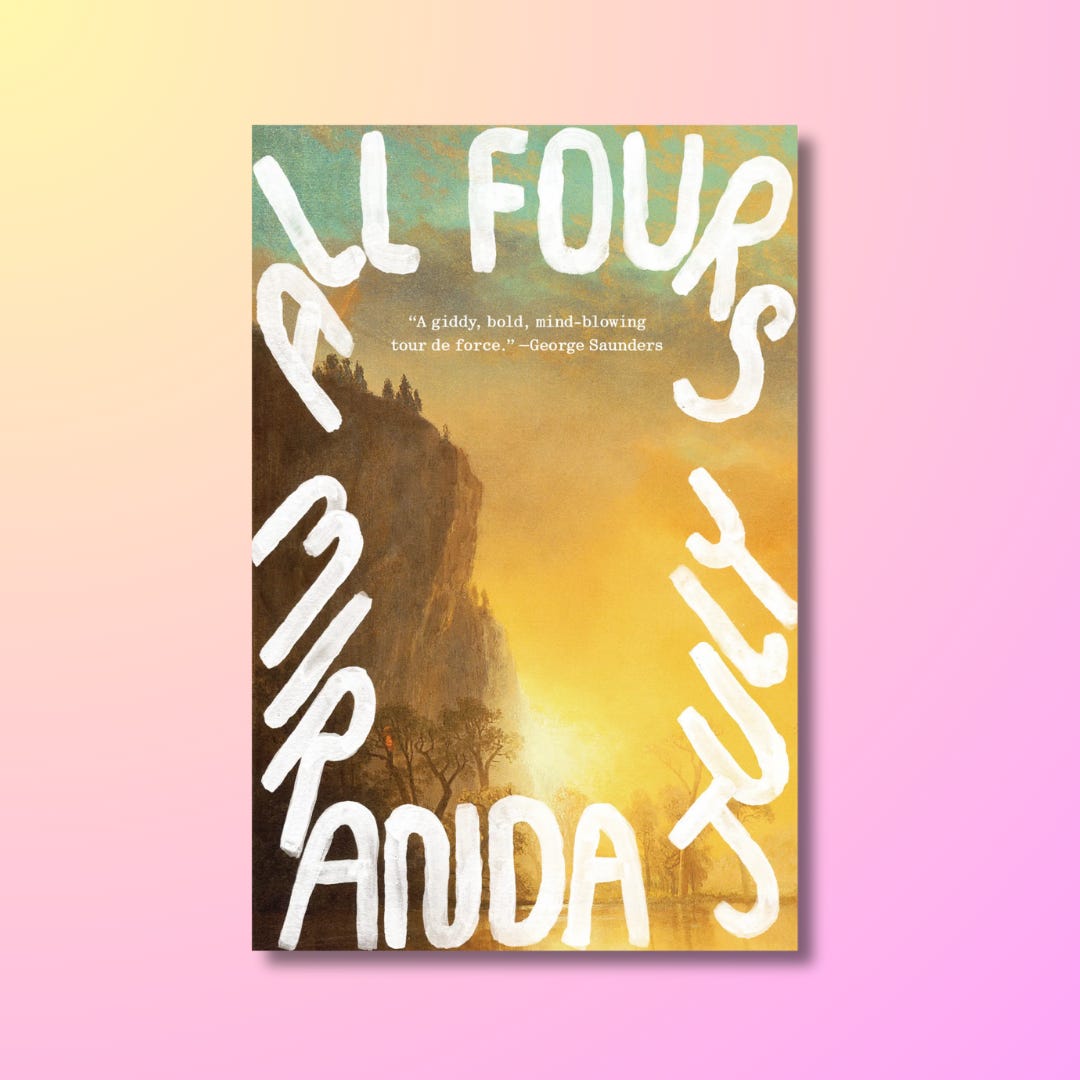

There is a scene in Miranda July’s brilliant new novel All Fours where its unnamed female protagonist, suffering from a severe dose of lust, maybe love and sexual frustration, and living in fear that this will be her last chance to feel pleasure, can’t stop cleaning. She becomes obsessed not just at the thought of having sex with another man she has met by chance, but also with her own sexual desire and the fear that it could fade at any moment due to her newly discovered perimenopausal state. She tries various ways to move on, including cleaning:

I scoured and polished like a woman who had only her floors to be proud of. I attacked the refrigerator and freezer, our closets, junk drawers—all the places a happy person would never go […] I simply told myself what I wanted to have done and I obeyed, with no feeling about it one way or the other. I went room by room: every drawer, floor, cabinet, shelf, window. I wasn’t fast or engergetic, just methodical—the duitable servant of a future, unheartbroken self.1

She cleans to stave off her extra-marital desire and her obsession— as if the ultimate act of homemaking and good-wifery will prevent her from thinking about the man she is infatuated with — as if cleaning might take her someplace new, make her someone new. Through her cleaning she hopes to become ‘unheartbroken’ — to get better. Become a happy person again, the sort that doesn’t clean. Yet this state of almost devotional, ritualistic cleaning also points to the ways in which cleaning, or any practical menial tasks, if performed with the right level of attention and inattention, can be a way to lose the self entirely. Cleaning is freedom from decision-making, from life in general, which is nothing if not a series of constant decisions. She does not have to think, only do. It is a release; a relief, to clean.

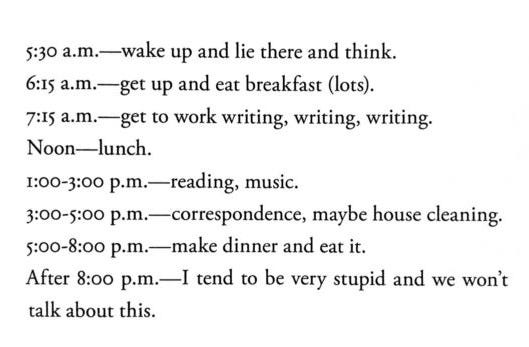

I hate cleaning, I like having cleaned. I hate writing, I like having written. Cleaning and writing is an investment in some future, better self as July points out. You have to trust the process. Ursula Le Guin knew this (see above) and Lydia Davis knows this. Davis also knows that the loss of the self, or rather the loss of the conscious self, is an important step in allowing one’s creativity to linger and expand during the pursuit of art. In her essay Thirty Recommendations for Good Writing Habits she cautions against allowing conscious life to slip back in after writing2 and suggests instead practical activities, including cleaning, to invite one’s ideas to percolate:

Important practical tip: After a session of writing, leave some clear time in which you can note down what your brain will continue to offer you. In other words, do not go directly from writing to lunch with friends or a class. Do not go straight to your emails or your phone. Leave at least fifteen minutes completely open. Do the dishes or take a walk or a shower—do something physical in which you can remain open to your random thoughts. Your brain will offer you a few more good ideas during this time. Don’t lose them by silencing them with other activities.3

On Mondays, I have the day off work and I set aside my morning to write — if I am on a deadline the whole day and evening is given over to this task of ‘writing’. But more usually, if I am free to schedule my day as I wish, I write from 8 am until lunch (or rather I sit at my desk between those hours, what actually happens there is none of your business) and I consider that an acceptable amount of ‘writing’ for one day.

In the afternoon I usually do household chores: washing up, the laundry, I pop to Aldi, I put the clothes away that have dried days and days ago. I temper this domestic labour with breaks to read or take the dog out or more usually play video games and craft while watching a YouTube video about video games. If I am feeling particularly martyrish and the dust has taken on a life on its own in the corners of our flat I might hoover. I have never cleaned our oven. I haven’t even checked if it is a self-cleaning oven. On a good Monday I will feel a sense of achievement both mental and physical.

But still, given the choice, I would rather spend my time doing almost anything else.4 Cleaning in our house often involves the scooping up of little threads and loose bits of cotton, the leftovers from our sewing and crafting. Evidence of just some of those things we would much rather be doing. When people ask me what it’s like being married to another woman, I usually say it’s no different, we still argue about who does the washing up. There is an assumption that our domestic life must be much easier. I have no yardstick to compare really, but I don’t think it’s all that different. The dirt still accumulates.

We did recently, finally, tidy our spare room. A task that has been on some vague to-do list ever since we moved in. Previously we had carved out enough space for a desk and our joint craft supplies and then slowly over the years the room simply filled up with all the sorts of things you don’t want to get rid of but also, crucially, don’t want to see every day. Clearing out a junk room is no mean feat but we managed it over several weekends and only slightly fewer arguments.

Like all attempts at tidying (see reality TV shows such Tidying Up with Marie Kondo or Get Organized with the Home Edit for this on a mass scale) at the apex of ‘having a tidy’ there is always a moment when everything suddenly looks much, much worse than when you started. Whereas before your belongings had been artfully hidden behind doors and drawers they now rest in messy heaps on the floor, mixed in with the rubbish and bags to go to charity. Now the outline of dust and grime is visible from furniture that has been moved after many years undisturbed. The temptation here of course is to stop. To lose faith. You must resist. Because things have to get much worse before they can get better.

Writing, is the same, editing even more so. Several times in the course of writing my book I despaired that I had ‘broken’ it — by which I mean in trying to make it better, cleaner, tidied, edited — I had moved the words and paragraphs around so much they were now all in little heaps of text, unmoored from one other and lacking sense. Like a unpacked suitcase on a return flight, I could no longer stuff the words back into the shape they once were. The only way through is forwards. You must cast off any affection for the old order. That’s gone now and it was wrong anyway.

This kind of editing, big structural edits and last-moment Hail Mary rewrites, requires faith in your ability to mend: to stitch together paragraphs from the ghosts of your own ideas and create something coherent. This stray thought floating in this chapter actually goes with this one over here — you add a little bridge to jump the gap and by some miracle, we have ended up at someplace new. It all looks so much worse before it gets better. You have to trust the process. Every time it feels like pulling off a magic trick. And then when you are done, if the magic trick has worked, you cannot even remember how it used to be. I hate writing, I like having written.

I’m sure the spare room is now the nicest room in the house.

All Fours, Miranda July, 2024, p. 155

If you need proof: I am writing this at 7 am, running backwards and forwards between the kitchen as I make breakfast, another thought occurring as I butter the toast, requiring a dash back to my keyboard.

Essays, Lydia Davis, 2019, p. 241.

You may have noticed I have avoided mentioning paid domestic labour — it is a topic far too complex to cover in this tiny newsletter.

really loved this piece x it really does have to get worse before it gets better.