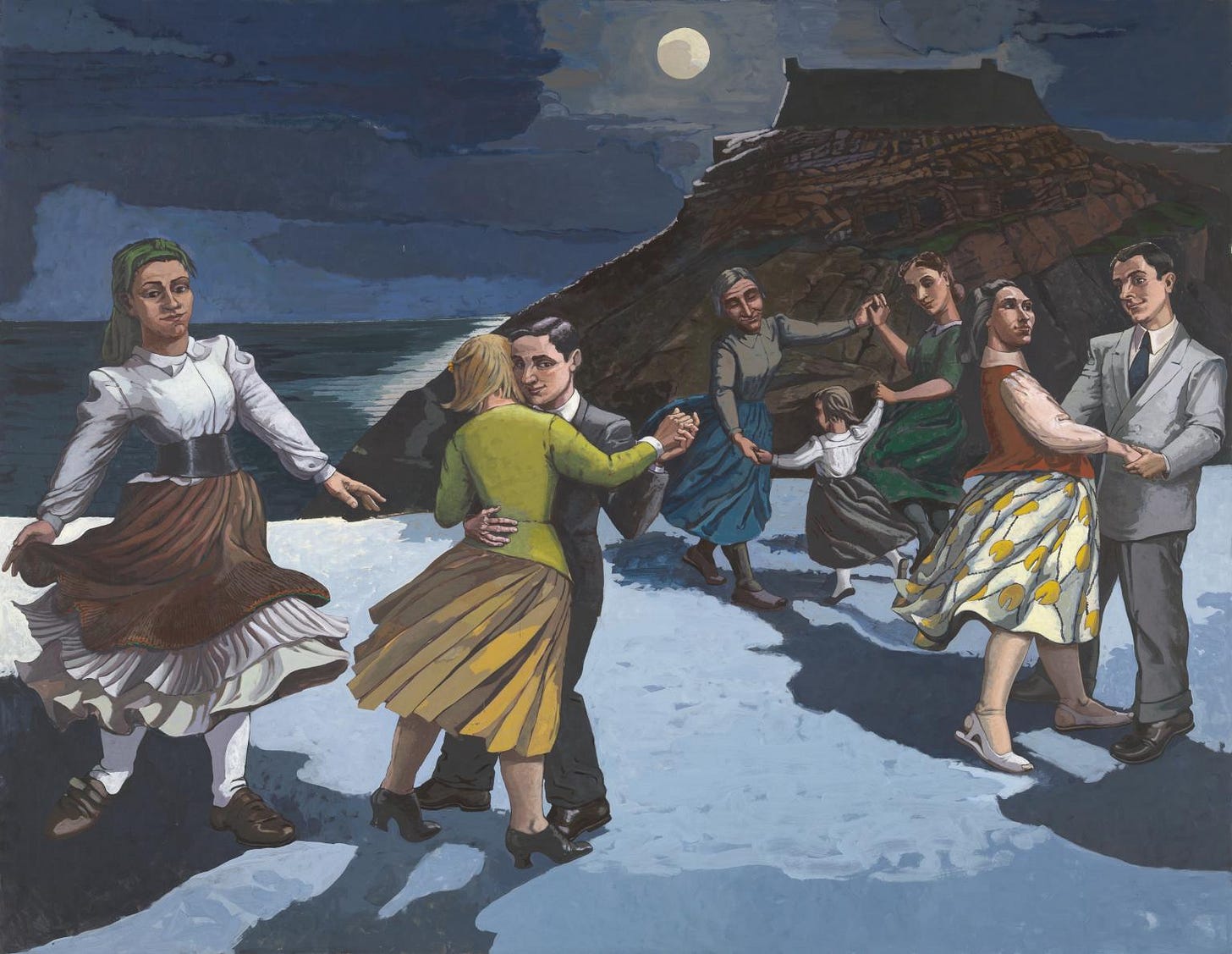

I wrote half of this review back in October, exactly a week after I went to see Paula Rego at Tate Britain. I was going to write about Rego as a storyteller painter and the appeal of her figurative paintings that (seemingly) in both a straightforward and allegorical way communicate a narrative to the viewer. How her paintings for me invite reading but resist imposing too much meaning. I was going to write about the fairy tale room in particular because I’m a basic English Lit grad who loves a feminist spin on a fairy tale. About how she conjures up these re-tellings across large multi-panelled canvases of grotesque figures, ripped from the pages of Snow White and bursting across the surface: about the dwarves that leer out from the canvas and how it’s impossible to say who is the fairest of them all. Or how she reminds us of the cruelty of nursery rhymes in her etching depicting three blind mice: hewn out in sharp black and white edges, their tails chopped off by the terrifying knife-wielding farmer’s wife behind them.

And then I got distracted by the way Paula Rego paints hands.

It was the fault of one painting in particular, The Artist in Her Studio, painted in 1993 as part of her tenure as the first artist-in-residence at the National Gallery. I stood for a long time in front of this maybe self-portrait, a vanitas painting filled with symbolic objects. It’s the painting from the posters and the catalogue cover so you know it’s a biggie. And it’s an obvious choice since it depicts the maybe-Rego as you expect her to be from her paintings: solid, robust, legs skirted but spread wide, head to one side and holding a pipe to her lips. She is surrounded by the artefacts of her trade. Sturdy is the word that springs to mind looking at that painting. An artist in their element. And I couldn’t stop staring at her hands.

Once you notice the way Rego paints hands you can’t unsee them. Larger than life and universal, whether they are holding the hand of a lover, plucking a swan or bracing themselves against the floor. There’s no difference between the hands of men and the hands of women. No one ever holds anything loosely in her work. Hands as big as dinner plates, they grasp and twist at objects and each other within the frame. I couldn’t stop staring at all the hands on display. Rego paints hands in a way that is mythic and sexy and confrontational and deliberate.

I don’t really have anything smart to say about the way Rego paints hands, or what that means or what the story there might be. I can only say that I liked them very much. I thought they were good representations of hands. That the more I looked at the hands of the women and men and unknown things as I moved from room to room the more I felt moved by them in some sort of way. An appreciation I think of her artistry, a recognition of the human body, my body, my hands, that did not look like that but felt like they too could do something meaningful and strong and certain on occasion. A recognition sprung up in me in the wordless way that art sometimes allows that yes, this was right and good that Rego should paint hands the way she paints them. That the hands that made those hands did well and that was enough.